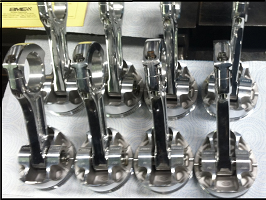

The Racepak graph below is of a dragstrip pass with an engine that puts out around 425ftlbs max WOT steady state. I added some averaged binary torque numbers to the lower part of the graph to reflect the calculated torque that the engine applied to the transmission's input shaft during the pass. Note how this 425ftlb engine put out way more than 425ftlbs when it is losing rpm, and much less than 425ftlbs when it is gaining rpm. At no time during this pass was this 425ftlb engine actually sending 425ftlbs to the transmission's input shaft, because at no time during this pass was the engine operating at a constant rpm. The engine was either losing or gaining rpm at every point after launch while it worked its way thru the gears. Note that during the climb in 1st gear, less than half of that engine's potential torque output was actually reaching the transmission's input shaft!

...you might ask- If this Engine is capable of 425ftlbs, WHERE DID ALL THAT MISSING TORQUE GO???...

To wrap your head around this, it helps to think of the engine's rotating assy as a torque storage device. Everything spinning ahead of the transmission's input shaft, crankshaft/balancer/pulleys/flywheel/pressure-plate/etc, it's all basically one big energy storing flywheel. The reality is that some of this engine's torque was being absorbed by its rotating assy as it gained rpm, and then that absorbed/stored torque was returned as rpm was drawn out of that engine's rotating assy against WOT.

From there, it's important to understand that the rate that the clutch draws engine rpm down is what controls how that absorbed/stored torque gets applied to the transmission's input shaft. Using nice round numbers to make it easy to grasp the inverse relationship, let's say a rotating assy gains 2000rpm in 1 second while absorbing 200ftlbs of torque during the engine's climb to the 1/2 shift point...

...If the clutch then draws out the same 2000rpm over the same 1 second time period after the shift, 200ftlbs gets added back to the input shaft torque for 1 sec.

...If the clutch then draws out 2000rpm over 0.5sec, 400ftlbs of torque (double the torque) gets added to input shaft torque for that 0.50sec.

...If the clutch then draws out 2000rpm over 0.25sec, 800ftlbs of torque gets added to input shaft torque for that 0.25sec.

All three above examples of discharge rate release the same quantity of energy. Give the car 200ftlb "boost" for 1sec (200 x 1 = 200), vs a 400ftlb boost for .5sec (400 x .5 = 200), vs an 800ftlb boost for .25sec (800 x .25 = 200), it's all basically the same amount of boost available from 2000rpm's worth of returning energy.

When you go beyond daily driving and move to the track, drawing that stored energy out too fast can cause other problems downstream. The initial problems are likely to be either traction or finding weak links in your drivetrain. If the tires go up in smoke, the typical solution is to buy better tires. If the problem is wheelhop, new bushings/shocks/chassis components. If the driveshaft or u-joints fail, bigger/stronger parts. If the transmission breaks, stronger trans. Break rear gears/diff/axles, spend another pile of money on a rear upgrade. But even after you get all those things sorted out, you will find your combination is still not performing to its potential, as now the engine bogs. But when the root cause of the cascading problems is an overkill clutch that draws too much torque from the rotating assy, addressing that problem first could save you from making a lot of un-necessary upgrades.

Given that a 2000rpm discharge releases the same basic quantity of energy regardless of how fast you lose the rpm, you have to ask yourself how big of a torque spike can your drivetrain/chassis efficiently handle? Are the tires going to be shocked into excessive wheelspin and waste a large portion of the returned energy? Is it going to break something? Would it be better to use a clutch that draws 400ftlbs of stored energy over 0.50sec rather than one that draws 800ftlbs over 0.25sec?

What about heat, isn't more slipping going to damage the clutch? Using your brakes also creates heat and shortens brake life, but as long as you do not overheat them they will last a good long while. Same with a clutch. Extending clutch slip time just a few tenths of a second can make a huge difference in terms of impact on your drivetrain.

If you are not slipping something in a drag race scenario, you are slow!!! While a properly slipping clutch does "waste" some power that gets absorbed into the clutch assy as heat, that slipping actually makes it possible to net an overall power production gain. That's because slipping allows the engine to make more power strokes in a given time frame, and that power production gain can more than offset the loss of heat energy absorbed by the clutch. Also because the car is gaining speed while the clutch is slipping, engine rpm does not get pulled down as far after the shift as the ratio change predicts, further raising average rpm. It is possible for the clutch to slip too much and squander your power production gains, the trick is finding the sweet spot.

Chapter 01- The Basics of Inertia Management

Chapter 02- Calculating Inertia's Effect on Input Shaft Torque

Chapter 03- Clutch Slip After the Shifts... Good or Bad?

Chapter 04- Heavier Cars LESS Likely To Break Transmissions?

Chapter 05- Understanding The ClutchTamer

Chapter 06- Understanding The Hitmaster

Chapter 07- The Basics of Analyzing Dragstrip Data

Chapter 08- Flywheel Weight- Heavy or Light?

Chapter 09- Choosing a Proper Clutch & Pressure Plate

Chapter 10- The Importance of a Clutch Pedal Stop

Chapter 11- What's the Best Launch RPM?

Chapter 12- Do You Need a 2-Step Rev Limiter?

Chapter 13- Traction Problems- Adjust Shocks, Chassis, or Clutch?

Chapter 14- Are "Clutchless" Shifts Right For You?

Chapter 15- Traction Control- Yes or No?

Chapter 16- Apply ClutchTamer Tech to an Adjustable Clutch?

CHANGING THE GAME ON LAUNCHING YOUR STICK SHIFT CAR!!!