A clutch's torque rating gives the typical clutch buying customer confidence that the clutch they choose isn't going to slip against the torque their engine is capable of. If the clutch breaks something else downstream, at least the customer won't come back complaining about a weak clutch. The typical aftermarket clutch buyer doesn't realize a proper drag racing clutch is one that WILL slip when the clutch is dumped. In reality, choosing a proper clutch for drag racing is about more than just engine torque.

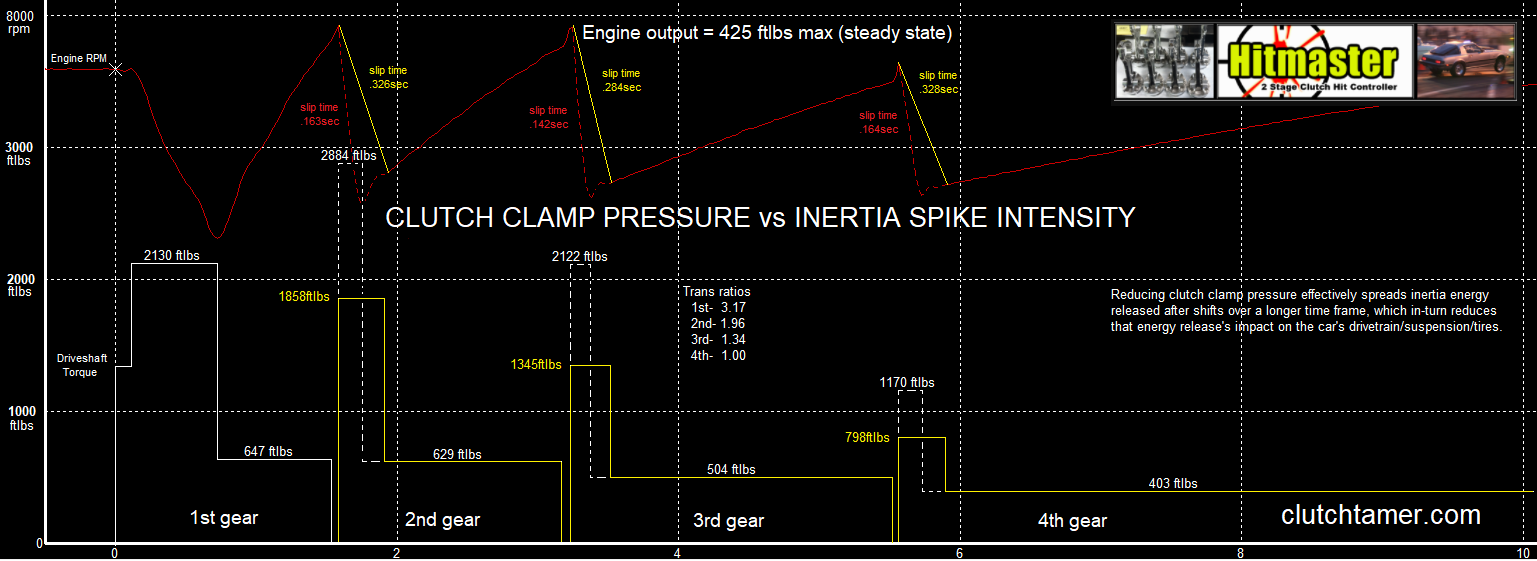

The Borg Warner T5 5spd serves as a good real-world example as to how too much clutch torque capacity can affect the durability of a transmission. It was an OE transmission for both GM and Ford, and the 2.95 gearsets for both GM and Ford applications are nearly identical as far as case/gear strength. While the GM version of the 2.95 V8 T5 has a reputation as being weak, it's pretty common to see the Ford version of the 2.95 V8 T5 running 10's on the dragstrip with slicks. The difference is the clutches that are commonly used with each version. The GM T5 guys almost always go aftermarket with around 2800lbs of clamp on a 10.5" organic disc, while the go-to clutch for the Ford T5 guys was the Ford Motorsport "King Cobra" with 2124lbs of clamp on a 10.5" organic disc. In reality the King Cobra was enough clamp for a 500ftlb engine, but the GM guys never discovered it as the Ford pressure plate did not fit their GM bolt pattern.

The clutch's basic job in a drag race setting is to allow the engine to operate near its power peak, with a goal of maximizing power production, hopefully without exceeding that clutch's thermal limit. Too much clamp pressure will pull inertia out of the engine's rotating assy too fast, which in-turn leads to bog/spin problems. Too much clamp pressure also narrows the sweet spot for clutch modulation, leading the clutch to act more like an on/off switch when casually driving.

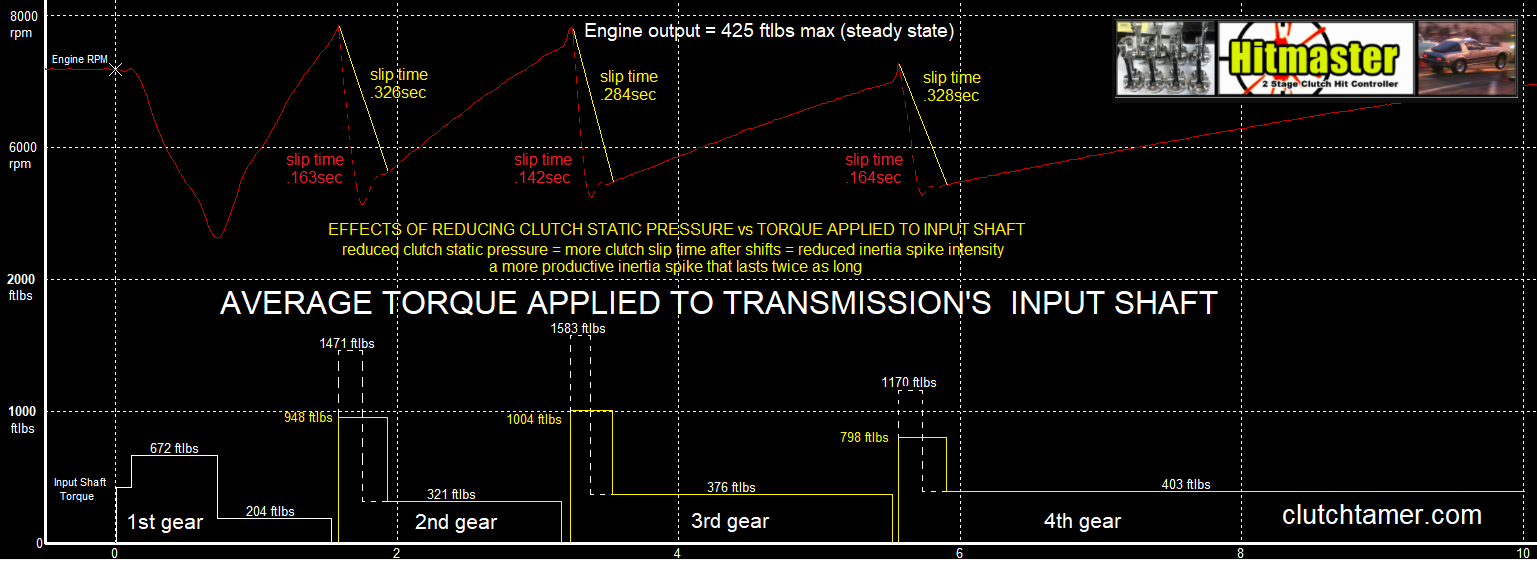

While a properly slipping clutch does "waste" some power that gets absorbed into the clutch assy as heat, that slipping actually makes it possible for the engine to make more power. That's because slipping allows the engine to make more power strokes in a given time frame, and that power production gain can more than offset the loss of heat energy absorbed by the clutch. Also, because the car is gaining speed even while the clutch is slipping, engine rpm does not get pulled down as far after the shift as the ratio change predicts, further raising average rpm. It is possible for the clutch to slip too much and squander your power production gains, the trick is finding the sweet spot.

Bottom line is, don't buy a clutch with plans to "grow into it". The target should instead be a clutch that slips for a half second or so after a WOT shift into high gear.

The purpose of optimizing clutch clamp pressure in a drag race application is not to protect the rest of the drivetrain from impacts, that side effect is just a happy by-product. The real purpose is to make the car quicker by improving traction and optimizing the engine's power production. While it may be counter-intuitive, a softer hit on the drivetrain CAN make your car quicker to the 60'!

Aftermarket clutch manufacturers typically rate their clutches conservatively. Can't blame them, as the typical customer doesn't want a clutch that slips, and the manufacturer doesn't want a dissatisfied customer. But if you are serious about not leaving any ET on the table, you need to push beyond those manufacturer ratings.

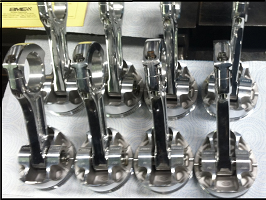

For example, the typical aftermarket GM/Mopar pattern 10.5" diaphragm PP installed out of the box has about 2800lbs of clamp. It's hard to find anything less in the aftermarket, so let's see what 2800lbs of clamp gets you with different types of clutch discs....

Let's say your engine puts out 500ftlbs, how much clamp would you then need for a typical dual friction disc? For that you can calculate a percentage of the above ratings. The above says 2800lbs of clamp on a dual friction disc is ballpark for 655ftlbs. If you divide 500 by 655, you get .76 which means you would need 76% of 2800lbs or 2800 x .76 = 2128. In other words, a 500ftlb engine needs about 2128lbs of ballpark clamp on a 10.5" dual friction disc. Good luck finding that in the aftermarket.

The above clamp numbers get you in the ballpark. Ideally though you are not looking for a specific clamp number, you are actually looking for a clutch that has just enough overall clamp pressure to pull the engine down in about 1/2 a second after a WOT shift into high gear. The actual amount of clamp required to do that will vary with gearing and rotating assy weight.

Another important thing to note is how the pressure plate's spring design affects clutch clamp pressure and tuning window as the clutch disc wears...

In general, regarding clutches that are installed out of the box without any PP shimming...

If you want the clutch to perform at its best throughout the life of the disc, periodic maintenance shimming of the pressure plate is one way to keep clamp pressure in its optimum range for a wide tuning window, regardless of disc thickness.

If you shift using the clutch pedal and don't want to go to all the trouble of dialing in your clutch's static clamp pressure, installing my ClutchTamer product is an alternative that will allow you to soften the hit of your clutch after the shifts from your driver's seat.

...With an organic disc, 2800lbs is ballpark for an engine with around 500ftlbs of torque.

...With a typical dual friction disc, 2800lbs is ballpark for an engine with around 655ftlbs of torque.

...With a typical iron puck disc, 2800lbs is ballpark for an engine with around 810ftlbs of torque.

...With a cerametallic puck disc, 2800lbs is ballpark for an engine with around 820ftlbs of torque.

...Diaphragm PP springs are typically designed to go "over-center" around mid-point in their travel range. They start out gaining clamp pressure as the disc wears, then at about the mid-point of disc wear the pressure curve levels out and begins to gradually lose clamp pressure for the rest of the disc's life. Basically, you end up with about the same static clamp pressure at the end of the disc's life as you had when it was new.

...B&B and Long style PP coil springs gradually lose clamp pressure as the disc wears. That means you must start out with a wide margin of extra spring pressure when the disc is new, just to have enough static clamp pressure to hold at the end of the disc's life when it is thin.

Hypothetical example of why this is important to understand- let's say a given combo wants 2800lbs of single disc clutch clamp pressure to hold after the shift into high gear.

...With a typical diaphragm spring, you need 2800lbs of pressure plate with a new disc, in order to have about 2800lbs at the end of the disc's life.

...With coil springs, you might need 3500lbs of pressure plate when the disc is new, in order to still have 2800lbs of clamp available when the disc is used up.

...A diaphragm sprung clutch that is closely matched to its application will have a wider average tuning window over it's life, as clamp pressure varies less over the life of the disc.

...A coil sprung PP starts out with a narrower tuning window when new due to excessive clamp pressure, then that window gradually opens up as the disc wears. Generally, a well-matched out of the box coil sprung clutch will perform its best just before the disc is worn out.

Here's a link to the ClutchTamer's information page "CLICK HERE"

Matching a clutch's static clamp pressure to its application has a huge effect on how easy that clutch will be to tune. Say you install a 1200ftlb capacity dual disc clutch behind a 600ftlb engine, the tuning window for that application is going to be very narrow, which will in-turn make it very hard to find and consistently hit the sweet spot. Ideally, you want the clutch's overall torque holding capacity to be well matched to its application, which will give you the widest possible tuning window.

As you can see, proper clutch clamp pressure also greatly reduces the chances of breaking your transmission/drivetrain! Here's how that change in base pressure would affect the torque applied to the driveshaft...

Doubling clutch slip time basically cuts the intensity of the inertia spike in half. This makes the car far less likely to knock the tires loose after the gearchanges, which in-turn makes the clutch's sweet spot much broader and easier to hit.

Chapter 01- The Basics of Inertia Management

Chapter 02- Calculating Inertia's Effect on Input Shaft Torque

Chapter 03- Clutch Slip After the Shifts... Good or Bad?

Chapter 04- Heavier Cars LESS Likely To Break Transmissions?

Chapter 05- Understanding The ClutchTamer

Chapter 06- Understanding The Hitmaster

Chapter 07- The Basics of Analyzing Dragstrip Data

Chapter 08- Flywheel Weight- Heavy or Light?

Chapter 09- Choosing a Proper Clutch & Pressure Plate

Chapter 10- The Importance of a Clutch Pedal Stop

Chapter 11- What's the Best Launch RPM?

Chapter 12- Do You Need a 2-Step Rev Limiter?

Chapter 13- Traction Problems- Adjust Shocks, Chassis, or Clutch?

Chapter 14- Are "Clutchless" Shifts Right For You?

Chapter 15- Traction Control- Yes or No?

Chapter 16- Apply ClutchTamer Tech to an Adjustable Clutch?

CHANGING THE GAME ON LAUNCHING YOUR STICK SHIFT CAR!!!