They may be described as "fully adjustable centrifugal assist" clutches, but they don't give you enough adjustment to allow taking full advantage of a hi-rpm launch and then still hold after the shift into high gear. You can adjust them for one or the other, but you can't have both. A centrifugal assist clutch needs that rpm difference between launch and shift rpm, as that is what allows for a softer hit during launch while then keeping you from blowing thru the clutch in high gear. That's just one of the limitations that comes along with using counterweight to add clutch clamp pressure.

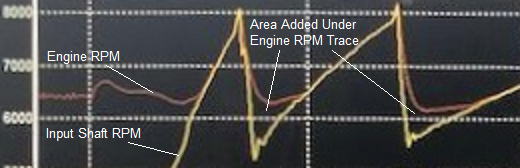

THE DOWNSIDES OF USING CENTRIFUGAL ASSIST - Rpm controlled centrifugal assist is generally used to prevent the clutch from pulling the engine down/out of its power range during launch. When adjusted as designed, centrifugal assist will automatically relax enough to let the clutch slip before the engine gets pulled below its torque peak. They also raise fallback rpm over that predicted by ratio changes after the shifts, which serves to increase the area under the engine's rpm trace. More area under the engine's rpm trace generally translates to more power produced in a given time frame.

......On the street- over about 1000hp, an adjustable clutch's drag strip tune is generally stiff enough for casual street driving. Mash the throttle to pass someone though, that race clutch tune is going to slip unless you downshift to pick up some centrifugal assist. In my opinion, 1000+ hp on the street looks kinda silly when it has to downshift to pass someone. To prevent that embarrassment, many street/strip racers find it necessary to adjust their adjustable clutches back and forth between street and race clutch tunes. That usually means jacking up the car to make the adjustments, which in-turn means a good jack and jack stands are required. Keep in mind that the engine has to be rotated to at least 6 different positions to facilitate the adjustments, also the danger of being under the car and forgetting to place the transmission in neutral before rotating the engine. That's a lot of extra hassle for a guy that wants to drive his car to the track.

......On the track- An adjustable clutch that actively relies on rpm to increase its torque capacity is less than ideal for drag racing. They were an improvement over earlier non-adjustable versions mainly because the clutch can be adjusted to slip below the engine's torque peak, which in-turn prevents the clutch from pulling that engine down out of its power range regardless of launch rpm. This also made it possible to adjust launch intensity simply by varying launch rpm. The downside is centrifugal assist clutch forces you to compromise on how much rpm you can bring to the starting line.

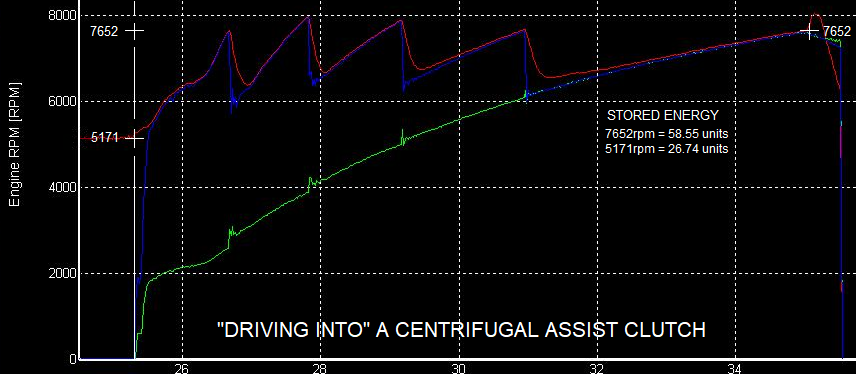

As the above graph shows, this adjustable centrifugal assist clutch equipped car launched from 5171rpm with very good efficiency considering the rpm that it launched from. One thing to note though is that it crossed the stripe at 7652rpm. That basically means that over the course of the pass, this engine's rotating assy absorbed 31.81 more units of inertia energy than it would have if it had launched from 7652rpm. If this car had been capable of efficiently launching from 7652 instead of 5171rpm, an additional 31.81 units of stored energy would have gone into accelerating the car instead of being absorbed by the engine's rotating assy.

The clutch's engagement characteristics and consequently how fast the clutch pulls the engine down during launch, as well as after the shifts, are among the most important adjustments you can make to a stick shift drag car. Torque x RPM, highest average number wins if you can get all that power to the track consistently. Raising launch rpm adds area under the engine's rpm trace, which means the engine will produce more power strokes in a given time frame. But what happens after the shifts can also add area under the engine's rpm trace.

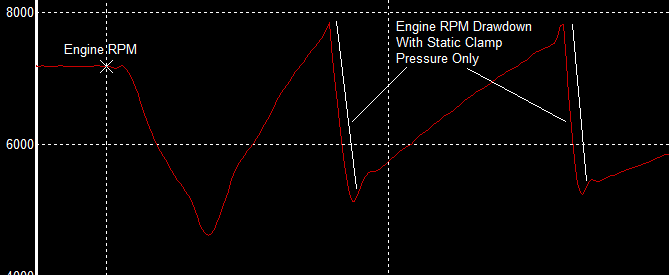

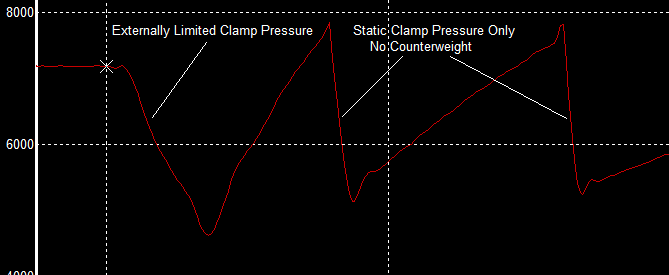

With the typical diaphragm, B&B, or Long style pressure plate (spring pressure only, no added centrifugal assist), the drawdown part of the engine rpm trace after the shift will be pretty linear, basically a straight line like on this graph below...

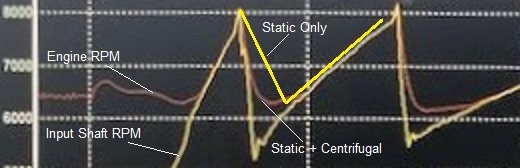

With a SoftLok style "adjustable slipper clutch" that uses counterweights in addition to spring pressure to clamp the disc, the drawdown part of the engine rpm trace will form a gradual curve. Because the centrifugal counterweight component relaxes as the clutch pulls engine rpm down, overall clutch clamp pressure relaxes as well. Note that engine rpm initially drops very quickly after the gear change (trace falls almost straight down initially), but then the trace begins to curve as the clutch gradually loses it's ability to pull the engine down any further...

An advantage of the curved engine rpm drawdown shape after the shift is that it adds area under the engine's rpm trace (more engine power strokes in a given time frame). If the clutch had not slipped at all after the above 1/2 shift, the ratio change dictates it would have pulled the engine down to around 5245rpm (input shaft speed) after the tires hooked back up. But because the SoftLok style clutch has an additional centrifugal component, clamp pressure gradually relaxed as the engine lost rpm, which in-turn gradually slowed down the rpm loss. Because the car was also gaining speed while the clutch was slipping, the delayed lockup point raised the minimum rpm after the shift to 6302 instead of drawing the engine all the way down to 5245rpm as predicted by the ratio change. That added clutch slip time effectively tightens up the engine's operating range, which in-turn allows the engine to operate higher on the plateau of its HP curve.

Going back to the static-only (no added centrifugal assist) straight line clutch graph, it's important to know that you can adjust the angle of engine rpm drawdown after the shifts by adjusting the clutch's static clamp pressure. Note on the below graph that the angle of drawdown after both shifts are basically the same, while the drawdown after launch is still straight but the angle is different as launch rpm was drawn out over a longer time period...

The above difference between launch and after shift drawdown angles was made possible by externally controlling throwout bearing position during launch. Basically the throw-out bearing was not allowed to fully retract during launch, which prevented the full force of the clutch's spring pressure from clamping the disc. The throw-out bearing was then allowed to retract shortly after launch, which in-turn increased the clutch clamp pressure available for the shifts. The angle of drawdown during launch is adjusted via throw-out bearing position, while the angle of drawdown after the shifts is adjusted via static clamp pressure. In the end you end up with more clutch slip during launch, and less clutch slip after the shifts.

Here's the SoftLok style curved drawdown shape compared to what the "static only" straight drawdown could look like if static clamp pressure were optimized. Notice how the "static-only" (no centrifugal assist) straight-line drawdown angle can be optimized to add even more area under the engine's rpm trace than the traditional SoftLok style curved drawdown. Also note that the initial drawdown after the shift is not as steep. That flatter angle indicates energy is leaving the engine's rotating assy at a slower rate initially, which in-turn makes it easier to keep the tires stuck thru the shift. Because the engine is producing power at a quicker rate during the optimized "static only" straight-line drawdown, the clutch lockup point occurs sooner, which then allows the engine to get a head start on its climb to the next shift point...

When you add external throw-out bearing position control to the "static only" (no centrifugal assist) straight-line drawdown, it allows you to take advantage of much higher rpm launches without knocking the tires loose. That adds even more area under the engine rpm trace without dragging the engine down. The resulting high rpm dead hook launch really shines on a crappy track, it also reduces the need to adjust tire pressure and launch rpm for the purpose of controlling wheelspeed. Without the need to control wheelspeed, you will likely be able to make use of less first gear ratio, which will in-turn allow tightening up the gear splits if that is an option for you. Little gains here and there, but it all adds up.

Like I said earlier, it will be far easier to tune your adjustable clutch if you just throw away the weights and then put just enough spring in it to hold after shifting into high gear. From there use one of my clutch hit controllers to control throw-out bearing position during launch. Completely eliminates the centrifugal vs base balancing act, as it allows you to adjust launch clamp pressure without affecting high gear clamp pressure. Far simpler way to tune a clutch, and you won't need help from an expert to dial it in.

......If it slips too much or not enough going into high gear, you know you need to adjust the spring pressure.

......If it slips too much or not enough during launch, you dial that in with the clutch hit controller from the driver's seat.

In the end its much like a quick automatic transmission car. A less efficient coupling (converter) allows the engine launch higher and gain rpm faster, while also reducing rpm loss after the shifts. The increase in power production shows up as more area under the engine rpm trace, and that added power production more than offsets the loss of mechanical efficiency.

In my opinion, below about 1200hp the traditional "adjustable slipper clutch" style centrifugal assist clutch tune is becoming outdated tech. First it limits your ability to take advantage of launch rpm, then it has a tendency to knock the tires loose after the shifts. Knocking the tires loose after the shifts is usually what prevents guys from making the switch to radials. Even if you have a modern ECU that allows momentarily reducing power to absorb the spike after the shifts, those momentary power reductions will still cost you ET vs a properly adjusted "static only" clutch that needs minimal or no power reduction after the shifts. Combine that with the ability to raise launch rpm by controlling throw-out bearing position during launch, the adjustable centrifugal assist feature in most cases becomes obsolete.

Chapter 01- The Basics of Inertia Management

Chapter 02- Calculating Inertia's Effect on Input Shaft Torque

Chapter 03- Clutch Slip After the Shifts... Good or Bad?

Chapter 04- Heavier Cars LESS Likely To Break Transmissions?

Chapter 05- Understanding The ClutchTamer

Chapter 06- Understanding The Hitmaster

Chapter 07- The Basics of Analyzing Dragstrip Data

Chapter 08- Flywheel Weight- Heavy or Light?

Chapter 09- Choosing a Proper Clutch & Pressure Plate

Chapter 10- The Importance of a Clutch Pedal Stop

Chapter 11- What's the Best Launch RPM?

Chapter 12- Do You Need a 2-Step Rev Limiter?

Chapter 13- Traction Problems- Adjust Shocks, Chassis, or Clutch?

Chapter 14- Are "Clutchless" Shifts Right For You?

Chapter 15- Traction Control- Yes or No?

Chapter 16- Apply ClutchTamer Tech to an Adjustable Clutch?

CHANGING THE GAME ON LAUNCHING YOUR STICK SHIFT CAR!!!